technoPHOBE

Building a Longbow

by Steve Struebing on Apr.09, 2008, under technoPHOBE

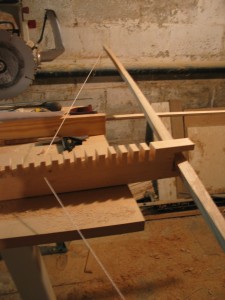

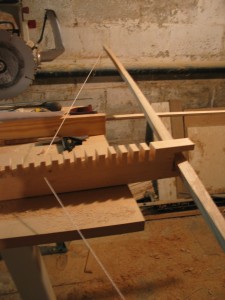

Longbow on tillering stick

Test Firing the Longbow

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkgmPqN8Q54

The Short of Longbow Building

There are many factors that affect the efficiency of the longbow. All things being equal, a heavier draw weight (the strength needed to pull the bow back to full draw length) yeilds a faster arrow. However, if the bow does not effectively transfer that energy quickly and effctively into the arrow, a lower draw weight bow will outshoot a heavier one.

- Draw Weight – as noted above – the heavier, the faster the arrow

- Draw Length– The longer the bow, the faster the arrow.

- String Height– This one may feel counter-intuitive, but a lower strung bow makes for a faster arrow.

There are many other factors regarding where the mass of the limbs is located, internal friction in the limbs, arrow mass, etc. If you are interested in all of those details, I leave it to the masters in “The Traditional Bowyer’s Bible” (yes, there are 4 volumes). Its easy to follow, and you’ll be amazed how complex this little machine is. Also, its amazing how the ancient cultures “happened” upon massive improvements such as the recurve, composite bow, and others. Neat stuff, but I digress.

Starting to Build

There is much to know about what to look for in the wood you use. It’s an artform in and of itself. Osage Orange and Yew woods are great traditional ones to use. For us, we used ash. To keep it simple here, the tree lays down a new ring each year (yeah, remember looking at cross sections and counting rings as a kid, right?). Ideally you want the “back” of the bow, which is the side facing away from the archer, to be one continuous growth ring. The back of the bow is under significant tension (where the “belly”, or side facing the archer, is in compression) so a single ring affords by far the best tensile strength. In this picture, we have cut the wood (called “the stave”) at an angle aligning with the growth rings to give us good strength.

Note the light and dark bands

Natural Born Tiller

We have created our profile of the bow, and marked off the taper to an appopriate notch size. Warm up the rasps and planes, because the hard work is about to begin.

Here we mark off the taper to the notches to be planed off.

This is where the real work begins. This is the process of “tillering” the bow. Once you have done what you can to get the back of the bow to a single growth ring (ours was not perfect, but good enough we hoped) the long process of reducing the belly begins. Using a rasp and plane (many bowyers are adept with a drawknife) we reduce the wood to it starts to bend, and place it on a “tillering stick”. This holds the bow in place and has inch by inch notches to draw the bow longer and longer back.

Here with the rasp, plane, and drawknife is the real work.

Longbow on tillering stick

As we plane and put the bow on the tillering stick, we are looking for places where the bow bends unevenly. That indicates there is too much wood on a limb of the bow, and needs to be balanced. Here is an example of a “hinge” that has developed due to uneven tiller.

Note the hinge that has developed on the bow. More work needed here.

Here the hinge has been tillered out of the bow.

Also you can get a sense of how the tiller is going doing by drawing the bow yourself. This bow was damn heavy at this point.

Testing the draw weight of the bow.

Finishing and Testing

After 8 hours of tillering (I don’t know what the average is, but I doubt it should have taken that long), we used a bathroom scale to test the draw weight at a given draw length. For us, we ended up with 45 pounds at 28 inches draw. Not a heavy bow (some of old English warbows were 100 pounds plus. Forget that image of little wussy archers in tights), but still seemed functional for a first attempt.

Testing the weight on the scale

Successfully firing the bow